A quick review of “Depth of Field”

Since the dawn of photography “depth of field” has plagued, puzzled, and aided photographers. A simple definition of depth of field, DOF, is the range in a photo from the closest to the farthest distance that is acceptably sharp. DOF is used to include areas in a photo as well as to exclude unimportant elements. For this second use the limit is then “acceptably blurred”. Simple isn’t so simple anymore.

For a very good overview with enough math to serve as a sleep aid for an insomniac (at the bottom, don’t worry the main part is easy enough), see this listing in Wikepedia – Depth of Field.

Another great tutorial is provided by Cambridge in Colour: Depth of Field.

Great depth of fields is what we want in our epic landscape photos that show everything tack sharp from in front of our feet to the farthest mountain. Here is a great example by Stephen Blecher:

B&W version by Ludwig Keck

Decades ago, in the days before zoom lenses and instant playback of the images, lenses featured depth of field scales or indicators to aid the photographers. Nowadays with zoom lenses that is not feasible, indeed many lenses have no distance scales, but that does not make DOF any less important.

As I said, depth of field is the range in a photo from the closest to the farthest distance that is acceptably sharp. This range is controlled by several factors. “Acceptable sharp” depends on how much the photo will be enlarged and human vision. Practically the detail in a photo depends on the pixel size of the camera sensor, the aperture of the lens, the focal length of the lens, and, yes, the “quality” of the lens.

Hyperfocal Distance

You can control the depth of field by the selection of the focal length, aperture, and focus distance. In days of yore, photographers were drilled the use of the “hyper-focal distance”. That is the focus distance, for a given aperture, that produces the maximum depth of field. For landscape photography that is the setting to use. You can bring flowers or plants close to the camera in focus and still render the distant mountains sharp.

For example for a 35mm lens on a full size sensor (24mm by 36mm) the hyper-focal distance at f/16 is about 8 feet, 2.6 meters. With the lens focused to that distance everything will be sharp from half that distance, 4 ft, 1.3 m, to infinity. At f/11 the hyper-focal distance is about 12 ft, 4m, with the DOF reaching down to 6ft or 2m.

In practical terms, if you want the distant mountains and something fairly close, don’t focus on the mountains, don’t focus on the close item. Focus in between so the depth of field includes the full range.

For a 50mm lens at f/16 the hyper-focal distance is about 20 ft, 6m, making the DOF from 10ft, 3m, to infinity. Notice that the DOF is less for the 50mm lens. It will be much less for longer lenses or lens settings.

But your digital camera most likely does not have a depth of field scale, it might not even have a focus distance scale. So how can you find and use the concept of hyperfocal distance? As you would expect, the Internet comes to the rescue. There are a number of sites with DOF calculators. One such is DOFMaster. You can download a program to calculate DOF and to print the graphics for a handy circular DOF slide rule.

If that seems like too much trouble, there is a simpler approach. You can find the hyperfocal distance from an on-line calculator at DOFMaster for your lens or lenses and jot down the hyperfocal distance for several f-stops.

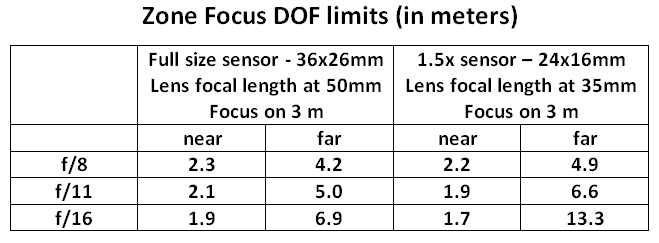

Here is such a table for two common sensor sizes. You will notice “CoC”. That is “circle of confusion”. The CoC is the diameter of the “smudge” on the sensor for the smallest spot that is to be perceived as a point in the viewed picture. Of course, there is a much more rigorous definition for that, but this will do for us. The adopted figures haven’t changed any in the past half century. For a full-size (36x24mm) sensor this normal figure is 0.03mm. What that says is that a picture that is 1000 pixels wide will have a pixel size corresponding to that CoC. Take another look at the photo above, it is 1000 pixels wide.

Even if your camera does not have a focus scale you can guess at something at the hyperfocal distance and focus on that.

Zone focusing for intermediate distances

Zone focusing for intermediate distances

Take another look at the photo of the camera lens scales above. The lens is set to f/16 and the focus distance to about 8 ft (2.4m), pretty close to what the table shows for the hyperfocal distance. But also note the numbers on either side of the ▲ mark. Those correspond to aperture f-stop values and the lines lead to the near (left side) and far (right side) depth of field distance limits.

For the focus setting in the photo the depth of field at f/8 will extend from a bit over 5 ft (1.6m) to about 15 ft (5m). That is a range of almost 10 feet (3 meters) where everything will be acceptably sharp.

For street photography this is the way to go!

Focus on the average distance of subjects you wish to photograph. Switch to manual focus and leave the focus set as is. Get an idea of the DOF range and keep your subjects in that zone and shoot away.

Close-up photography

At longer lens focal lengths, wider apertures and closer distances the depth of field is shallower. You can get an idea from the scale on the lens photo here. Indeed at very wide apertures and close focusing distances the depth of field may be down to millimeters!

This leads to another use of DOF: You can concentrate on just a narrow aspect of your subject making everything that is closer or farther blurred, out of focus.

Sometimes you can replace the background with a cloth or placard. But often that is not practical. So controlling the depth of field may be the way to go. You might want to set the depth of field for a specific range. What aperture should you use for a a given DOF? Again the on-line DOF calculator can help. Here is a chart that shows what aperture to use in order to get a DOF of 5 cm (2 inch) and 10 cm (4 inch) at a couple of working distances.

Here are three photos that control the depth of field so only the primary subject is sharp and the background is quite blurred.

Notice that the background consists of circles of light. Photographers call this “bokeh”. Wikipedia has a good article on bokeh. You can look it up. In effect these are images of the aperture in your lens.

The eagle photo was photographed at f/5.6 with a lens focal length of 200 mm. The magnolia blossom at f/16 and 55 mm, and the baby leaves at f/8 and 55 mm focal length.

If you are careful enough and have some control over the distance to the background you can get beautiful bokeh for most of your photos.

“Sweet spot” and diffraction blur

These are two more concepts that go hand in hand with depth of field. Every lens has an aperture setting at which the lens produces the sharpest image. Lens design is an art of compromise. To achieve the magnificent results that we accept as commonplace requires imaginative design, huge numbers of calculations that involve juggling of materials and production capabilities and many trade-offs. At the widest apertures lenses will have some limitations that prevent the image from being perfect. At small apertures the nature of light sets limits, this is diffraction. Diffraction is a blurring of light that prevents forming a perfect point. A point of light will be imaged as a small blurry circle or patch. At smaller apertures this patch gets bigger. So no matter how small the tiny pixel sensors are, the sharpness of the image will be limited. Diffraction blur starts to dominate for full-size sensor cameras at about f/16. For small sensors it will become the primary limitation at much wider apertures. This is why a photo taken at f/22 will not seem to be as sharp as one taken at f/11 or f/8. At wider apertures residual lens aberrations limit the sharpness. So for any lens there is a best aperture, the “sweet spot”. Take a look at the EXIF data for your sharpest photos. Keep the sweet spot in mind when you are taking pictures, try to use that aperture as often as possible.